Lab: Saddle point problems: Stokes Flow around a cylinder

Contents

Lab: Saddle point problems: Stokes Flow around a cylinder#

Overview#

In this lab, you will work with vector-valued finite element spaces to solve the Stokes Flow using the deal.II library. You will learn about reordering components in degrees of freedom based on FESystem to obtain block systems based on logical grouping of finite element components. You will also experiment with different finite element combinations, including inf-sup stable ones and not inf-sup stable ones.

Introduction to Stokes Flow#

Stokes flow, also known as creeping flow, refers to fluid flow regimes at very low Reynolds numbers, where inertial forces are negligible compared to viscous forces. This type of flow is characterized by its simplicity and is often encountered in applications involving very slow motion of fluids or small-scale systems, such as microfluidics, lubrication theory, and the motion of biological organisms in fluids.

Governing Equations#

The Stokes flow is governed by the following set of partial differential equations, which are a simplification of the Navier-Stokes equations:

Momentum Equation (Stokes Equation): $\( -\eta \Delta \mathbf{u} +\nabla p = \mathbf{f} \)$ where:

\(\mathbf{u}\) is the velocity vector of the fluid.

\(p\) is the pressure field.

\(\eta\) is the viscosity of the fluid.

\(\mathbf{f}\) is the external body force per unit volume (e.g., gravity).

Continuity Equation (Incompressibility Condition): $\( \nabla \cdot \mathbf{u} = 0 \)$

These equations describe the balance of forces in a viscous fluid where the flow velocity is low enough that inertial effects can be ignored.

Weak Form of Stokes Equations#

The weak form of the Stokes equations is derived by multiplying the momentum and continuity equations by test functions, integrating over the domain, and applying the divergence theorem. This process results in the following weak formulation:

Weak Form#

To derive the weak form, we introduce test functions \(\mathbf{v}\) for the velocity and \(q\) for the pressure, and multiply the momentum and continuity equations by these test functions. Integrating over the domain \(\Omega\) and applying the divergence theorem, we get:

Momentum Equation (Weak Form): $\( \int_\Omega \eta (\nabla \mathbf{u} : \nabla \mathbf{v}) \, d\Omega + \int_\Omega p (\nabla \cdot \mathbf{v}) \, d\Omega = \int_\Omega \mathbf{f} \cdot \mathbf{v} \, d\Omega + \int_{\Gamma_N} \mathbf{h} \cdot \mathbf{v} \, d\Gamma \)$ where:

\(\mathbf{u}\) is the velocity vector.

\(p\) is the pressure.

\(\mathbf{v}\) is the test function for velocity.

\(\eta\) is the dynamic viscosity.

\(\mathbf{f}\) is the body force per unit volume.

\(\mathbf{h}\) is the prescribed traction (Neumann boundary condition) on \(\Gamma_N\).

Continuity Equation (Weak Form): $\( \int_\Omega (\nabla \cdot \mathbf{u}) q \, d\Omega = 0 \)$ where:

\(q\) is the test function for pressure.

Combining these two equations, we obtain the coupled system in weak form:

Coupled Weak Form#

Find \((\mathbf{u}, p) \in \mathbf{V} \times Q\) such that for all \((\mathbf{v}, q) \in \mathbf{V} \times Q\):

Momentum Equation: $\( \int_\Omega \eta (\nabla \mathbf{u} : \nabla \mathbf{v}) \, d\Omega - \int_\Omega p (\nabla \cdot \mathbf{v}) \, d\Omega = \int_\Omega \mathbf{f} \cdot \mathbf{v} \, d\Omega + \int_{\Gamma_N} \mathbf{h} \cdot \mathbf{v} \, d\Gamma \)$

Continuity Equation: $\( \int_\Omega (\nabla \cdot \mathbf{u}) q \, d\Omega = 0 \)$

Here, \(\mathbf{V}\) is the vector-valued function space for the velocity field, and \(Q\) is the scalar-valued function space for the pressure field.

Boundary Conditions#

The weak form must be supplemented with appropriate boundary conditions:

Dirichlet Boundary Conditions (No-slip): \(\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{u}_D\) on \(\Gamma_D\)

Neumann Boundary Conditions (Traction): \(\mathbf{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{n} = \mathbf{h}\) on \(\Gamma_N\)

where \(\mathbf{\sigma}\) is the stress tensor, and \(\mathbf{n}\) is the outward normal vector on the boundary.

This weak formulation serves as the basis for the finite element method to solve the Stokes flow problem numerically.

Salient Characteristics of Stokes Flow#

Linearity:

The Stokes equations are linear in terms of the velocity and pressure fields, which simplifies their analytical and numerical treatment.

Reversibility:

The flow is time-reversible, meaning if the flow is reversed, it retraces its path exactly. This property is a direct consequence of the linearity and lack of inertial terms.

Dominance of Viscous Forces:

Viscous forces dominate over inertial forces, making the flow highly smooth and laminar. The Reynolds number (\(Re\)) for Stokes flow is much less than 1.

Boundary Layer:

There is no boundary layer separation as seen in high Reynolds number flows. The fluid adheres closely to the boundaries and obstacles.

Applications:

Stokes flow is applicable in various fields, including microfluidics, biological fluid dynamics (e.g., the motion of microorganisms), and porous media flow.

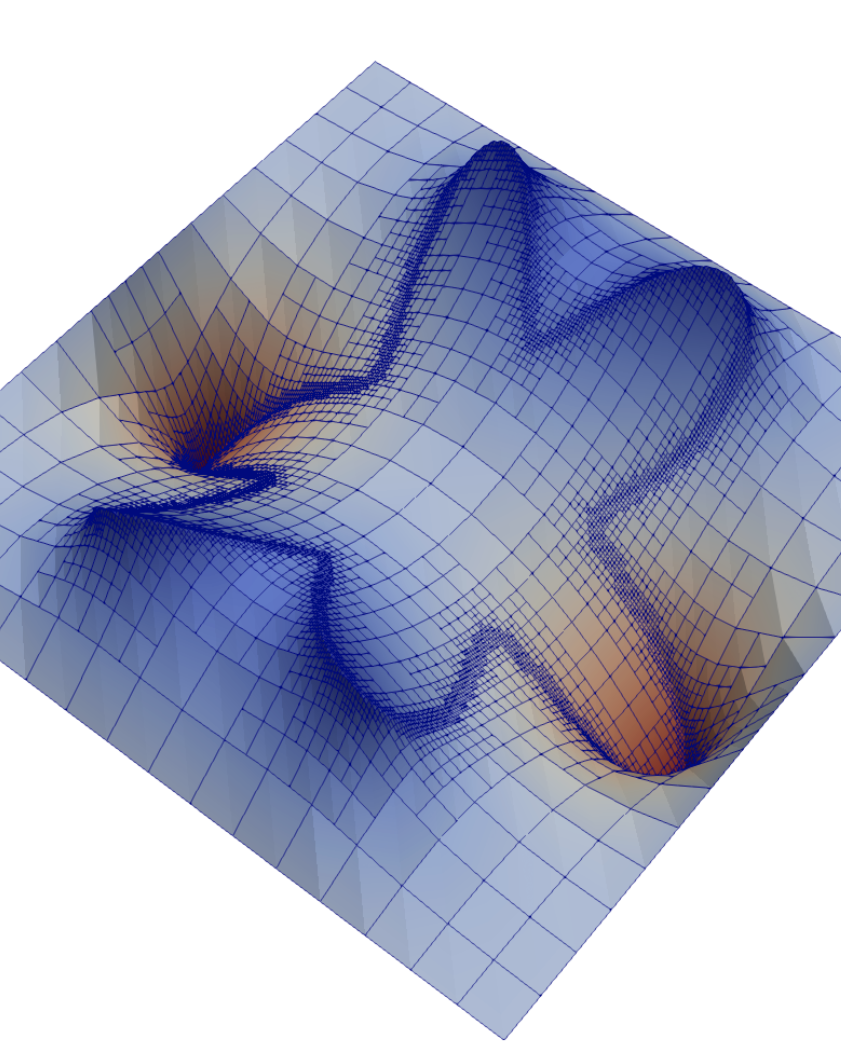

Example: Stokes Flow Around a Cylinder#

In this lab, we will focus on the classical problem of Stokes flow around a cylindrical obstacle within a channel. This setup is useful for studying how the presence of an obstacle affects the flow pattern in a viscous fluid. The cylindrical obstacle introduces complexity in the flow field, leading to the development of a symmetric flow pattern around the cylinder.

The boundary conditions for this problem typically include:

No-Slip Boundary Condition: The fluid velocity at the solid boundary (cylinder surface and channel walls) is zero.

Inflow/Outflow Boundary Conditions: Specified velocity profile at the inlet and zero normal stress at the outlet.

By solving the Stokes equations for this problem, we can obtain insights into the velocity and pressure distributions in the fluid, as well as the forces exerted on the cylinder by the fluid. This understanding is critical for designing and analyzing systems where low Reynolds number flows are prevalent.

Salient Changes for Vector-Valued Elements#

FESystem#

FESystem is used to create a vector-valued finite element space by combining scalar finite elements. In this lab, FESystem<dim> is created using a combination of FE_Q<dim>, FE_DGQ<dim>, and FE_DGP<dim> elements.

For example:

FESystem<dim> fe(FE_Q<dim>(par.fe_degree), dim, FE_Q<dim>(par.fe_degree - 1), 1);

This creates a vector-valued finite element space for velocity (dim components) and pressure (1 component).

FEValuesExtractors#

FEValuesExtractors are used to access specific components of the vector field in FEValues and FEFaceValues objects. For example, to extract velocity and pressure components:

FEValuesExtractors::Vector velocities(0);

FEValuesExtractors::Scalar pressure(dim);

These extractors can then be used to access the values, gradients, and other quantities of the respective fields.

Channel with Cylinder#

We will create a domain that consists of a channel with a cylinder at the beginning using the GridGenerator::channel_with_cylinder function from the deal.II library. This setup is commonly used to study flow around obstacles.

Add all respective parameters to the parameter file.

Dirichlet Boundary Conditions#

Dirichlet boundary conditions are imposed using AffineConstraints<double>, with the addition of one more argument to interpolate_boundary_values, corresponding to the finite element component mask to which we want to impose Dirichlet conditions (in this case, only the velocity):

VectorTools::interpolate_boundary_values(dof_handler,

id,

par.exact_solution,

constraints,

fe.component_mask (velocity));

Impose zero Dirichlet boundary conditions on the top, bottom, and cylinder walls

Impose inflow Dirichlet boundary conditions in the inflow boundary (inflow function from parameter file)

Impose zero Neumann boundary conditions on the outflow

Exercises#

Exercise 1: From Elasticity to Stokes#

Change the assembly and everything else you need to assemble Stokes instead of linear Elasticity.

Exercise 2: Explore the inf-sup condition of the problem#

Test the behaviour of the code for the following pairs of finite element spaces:

FE_Q(1)^d-FE_Q(1)FE_Q(1)^d-FE_DGQ(0)FE_Q(2)^d-FE_Q(1)FE_Q(2)^d-FE_DGP(1)

Make sure you can change the finite element spaces from the parameter file, using FETools::get_fe_by_name()

Exercise 3: Compute forces on the cylinder#

Integrate on the surface of the cylinder the term \(\sigma \cdot n\) where \(\sigma := \eta \nabla u\cdot n - p n\). This represents the forces experienced by the cylinder. If the cylinder is not in the center, the lift (vertical component of the force) should be non zero. Make sure your code behaves correctly from the physical point of view.

Exercise 4: Change domain#

Use the classes in GridGenerator::Airfoil to change the domain to a channel with a Naca Airfoil, and experiment with the possibilities given by that class. Compare the lift forces with the spherical case.